Celebrating the year’s most innovative examples of digitally enabled storytelling.

Columbia’s Digital Dozen: Breakthroughs in Storytelling Awards recognize signal achievements across the wide spectrum of media that rely on digital technologies, including cinema, video, journalism, advertising, marketing, games, art, fiction, virtual reality, and experimental narratives. In citing these accomplishments, the Lab hopes to encourage creativity and innovation while furthering digital media’s potential to break free of rigid, industrial-age classifications and evolve in ways that analog media could not.

The awards for 2015, the program’s inaugural year, were celebrated at the Film Society of Lincoln Center’s Elinor Bunin Munroe Film Center at an event that featured a roundtable discussion on the future of journalism with New York magazine editor Adam Moss and New York Times Magazine deputy editor Bill Wasik, as well as a conversation on art in the digital age with New Museum curator Lauren Cornell and Rhizome director Zach Kaplan. The presentation was subsequently featured in the Digital Storytelling Lab’s inaugural podcast, Crossroads, produced in partnership with the Film Society of Lincoln Center.

Columbia’s Digital Dozen for 2015 are:

Absolut Silverpoint, created by the digital agency Somethin’ Else (Paul Bennun, chief creative officer) and the immersive theater company Punchdrunk (Felix Barrett, artistic director) for Pernod Ricard UK.

Most advertisers seem to want to take over your screen. Not this one: As Brand Republic put it, “Absolut’s Silverpoint app has taken over our lives.” Developed to promote Absolut’s association with Andy Warhol, which began with the 1985 “Absolut Warhol” campaign and sparked subsequent collaborations with such artists as Keith Haring and Damien Hirst, Silverpoint was an iPhone game that turned into a story about a missing woman named Chloe and ultimately into a live theatrical experience by Punchdrunk, the company behind the long-running New York production Sleep No More. Players in London, where the Silverpoint story was centered, found themselves being led to pubs where, on being identified by Apple’s iBeacon technology, they were given a free drink. Those most committed to solving the mystery of Chloe’s disappearance ended up in the sub-basement of a Victorian shopping arcade in Islington with 15 or 20 others, one of whom would be hurled into a pit. (In truth the victim was a mannequin.)

Like much of the best digitally enabled storytelling, Absolut Silverpoint blurred long-established lines—between story and game, marketing and entertainment, digital and real. It was also remarkably successful. According to Somethin’ Else, more than 25,000 people downloaded the app; more than half of them played for at least five hours, and some 2,500 took part in one of the live events. The two-week campaign reached nearly three-quarters of London’s 25-to-34-year-olds, the dominant age group in the capital.

The Deeper They Bury Me: A Call from Herman Wallace, created by Angad Singh Bhalla and Ted Biggs for the National Film Board of Canada in association with Storyline Entertainment of Toronto.

Herman Wallace (1941-2013) was a Black Panther activist who went to jail for armed robbery and then spent 40 years in solitary confinement in Louisiana’s infamous Angola Prison for the murder of a corrections officer—a murder he maintained he didn’t commit. While making the 2013 Emmy-award-winning documentary Herman’s House, director Angad Singh Bhalla decided to tell Wallace’s story in a way that would reach people who might not watch an 80-minute film. The result is “The Deeper They Bury Me,” an interactive narrative that received its premiere at the 2015 New York Film Festival’s Convergence program, which celebrates innovators who blur the lines that once separated artistic disciplines.

What is it like to spend 40 years in a six-by-nine-foot cell? Bhalla used audio he’d recorded of Wallace for the documentary to simulate a phone conversation that users can listen to as they navigate his cell online. During the 20-minute call—the maximum time allotted for prisoners—Herman talks about how he maintained his sanity and how it feels to be led about in chains during the one hour per day he’s allowed “out.”

The Displaced, produced by Jenna Pirog of The New York Times and Samantha Storr of VR production studio Vrse, directed by New York Times foreign multimedia correspondent Ben C. Solomon and Imraan Ismail of Vrse for The New York Times Magazine; New York Times Magazine editor Jake Silverstein and Vrse CEO Chris Milk, creative directors.

As war and repression have transformed once-livable communities into horrific dominions of rape, murder, ruination, and despair, the world has become awash in refugees. There are more today—nearly 60 million—than at any time since World War II. Half of these are children. In November 2015, for its first virtual reality news story, The New York Times Magazine presented an 11-minute video that introduced readers to three of them: 11-year-old Oleg, who lives amid the ruins of his coal-mining village in eastern Ukraine; Hana, a 12-year-old Syrian girl who has spent three years living in a tent in a refugee camp in Lebanon; and nine-year-old Chuol, who fled into the snake- and crocodile-infested swamps of South Sudan with his mother and grandmother after soldiers raided their village and burned his father and grandfather alive.

State-of-the-art VR headsets not yet being commercially available, the Times distributed more than a million Google Cardboard viewers to its subscribers. Even this rudimentary device gave users a sense of presence that conventional video cannot provide: A scene in which sacks of food are air-dropped onto an island in the South Sudanese swamps, for instance, puts you right there, not viewing from the safe remove of a screen. Virtual reality remains an experimental medium, especially for narrative—but experiments such as this one demonstrate vividly what it can accomplish.

Door into the Dark, created by May Abdalla and Amy Rose of the UK studio Anagram.

For most of us, being lost is a discomfiting experience. May Abdalla and Amy Rose have managed to get people to line up for it. In April 2015, for its North American premiere in the Tribeca Film Festival’s Storyscapes competition, “Door into the Dark” induced festival-goers to take off their shoes, put darkened goggles over their eyes and headphones on their ears, and walk into the void alone with only a rope to guide them. As they felt their way through a labyrinth, iBeacons triggered the low, oddly soothing voices of individuals telling their own stories about what it means to be lost—a university lecturer who wrote a book about losing his sight, a mountain climber who nearly died, a man who ended up in psychiatric care after walking the streets at night in an attempt to lose himself.

Billed as “an immersive documentary experience about what it means to be lost in an age of infinite information,” “Door into the Dark” triggered a wide range of reactions—mild panic, disorientation, claustrophobia, compassion, wonder, euphoria, a sense of discovery and even liberation. “It offers a meticulously crafted storyworld that allows us to cerebrally, emotionally, and quite literally leave our baggage behind,” the Storyscapes jury said in awarding it the prize. “. . . Ambitious, simple, and profound, this work marks a fresh and promising direction for the field of immersive theater.”

Freedom, created by Josh Kline for the 2015 New Museum Triennial.

An artist who lives and works in New York, Josh Kline is concerned with, as he puts it, “technology changing what it means to be human.” He does not seem sanguine about the prospect. “Freedom,” a room-sized installation commissioned by New York’s New Museum for Surround Audience, its 2015 triennial, is dominated by four life-sized mannequins of cops in SWAT gear—cops with Teletubby faces and digital screens embedded in their midsections. These “tummy TVs,” inspired by the BBC’s whimsical late-’90s children’s TV series, play a video Kline calls “Privacy,” in which off-duty and retired police officers, their features disguised by face-substitution software, read social-media feeds that deal with police violence.

Playing on a screen behind them is another Kline video, “Hope and Change,” in which an actor disguised by the same software to look like President Obama delivers an imagined inaugural address—one that recalls the stirring oratory of his 2008 campaign rather than the tepid monologue he actually delivered on being sworn in. “I wanted to imagine Obama as the transformational political figure that America’s youth voted for in 2008—an FDR or Martin Luther King Jr. for the twenty-first century,“ Kline said in an interview that appeared in the triennial catalogue. The Teletubby riot squad, he added, shows people’s “lives, feelings, and beliefs being digested in the belly of the information police.”

The Hopscotch Opera, created by artistic director Yuval Sharon for the Los Angeles-based experimental opera company The Industry.

Inspired by the 1963 Julio Cortázar novel Hopscotch, which consists of 155 chapters and a table of instructions for skipping through them, The Hopscotch Opera was a series of 90-minute performances that took place in and around limousines traversing the streets of Los Angeles in October and November 2015. With four people per vehicle sitting knee-to-knee with singers and musicians, performances felt personal, even voyeuristic. The elaborately choreographed production included transfers from car to car and stops at such iconic locations as Elysian Park and the Bradbury Building (familiar to viewers of Chinatown and Blade Runner); wireless connections enabled performers on distant rooftops to stay in synch with one another. The story was told in 10-minute “chapters” that unfolded in a different order for each group, rendering the narrative fragmentary and nonlinear. Audience members had no idea where they would be taken next or what aspect of the story they would experience.

The effect was hallucinatory and surreal, with characters slipping in and out of alternate realities as well as unexpected insights into life in a car culture. “Driving along in a car with a man mourning his dead wife, accompanied by two violas . . . makes you suddenly, physically conscious of all the lives and sorrows and joys going on in all those cars driving past on the freeway all the time,” The Wall Street Journal concluded. “Mr. Sharon has broken the fourth wall with a vengeance.”

Karen, created by the UK artist group Blast Theory (Matt Adams, Ju Row Farr, and Nick Tandavanitj) in partnership with National Theatre Wales.

App stores for mobile devices sport a variety of “life coach” offerings—software that promises to help you be your best self. The members of Blast Theory, based in the English seaside town of Brighton, created an artwork in the form of one such app. While this app starts by trying to get to know you, it soon veers off into what might be considered inappropriate behavior. Blast Theory’s fictional coach—a young woman named Karen, played in the app’s videos by the British actress Claire Cage—turns out to have serious boundary issues. First she’s asking you about your childhood and your outlook on life; next she’s telling you about her recent divorce and her new roommate, a guy named Dave whose room is right down the hall. Not long after that she’s urging you to to help rifle his belongings while he’s out. How will you respond? The answer says more about you than the standard personality quiz ever could.

Ultimately, however, “Karen” is about humans’ relationship with technology. “We’re interested in the intimacy of mobile phones,” Matt Adams told Digital Storytelling Lab member Frank Rose for The New York Times. “How they might be thought of as a cultural space. ‘Karen’ was an opportunity to take this strategy further—how you might engage with a fictional character who is software-driven.” The answer is, with a great deal of ambivalence—which is precisely the point. “We know we’re making a satanic bargain,” he added, “but it’s a rich, murky space . . . something we’re very drawn to and very unnerved by at the same time.”

Life Is Strange, produced by Luc Baghadoust and directed by Raoul Barbet and Michel Koch for Paris-based Dontnod Entertainment.

At a time when a culture war has erupted among video gamers over the role of women, with female game developers and their supporters subjected to rape and death threats from anonymous protesters railing against “political correctness,” Life Is Strange seems an anomaly: a top-selling game in which the two protagonists are both female. Set in Oregon, it tells the story of a high school senior named Maxine who returns after five years away to find that her former best friend, Chloe, has become an angst-ridden pothead with blue hair and a roomful of missing-person flyers. The missing person turns out to be Rachel, Chloe’s new best friend and (probably) lover. Maxine, meanwhile, has learned that she has the ability to rewind time—a nifty game mechanic that enables the player to change outcomes almost at will.

Along the way, Life Is Strange deals with some strong stuff: Online bullying. Teen suicide (directly related). And, of course, being an adolescent girl in a male-dominated world. In this respect, art imitates life: The International Game Developers Association reports that only 22 per cent of game developers are women—and that’s double the figure from 2009. Not surprisingly, most video game characters are male. According to creative director Jean-Maxime Moris, every major game publisher except Square Enix pressured Dontnod to fall into line. Their refusal to comply hasn’t hurt them: Life Is Strange was one of the most popular games of 2015, selling more than 1 million copies within six months of its release.

Marchers protest the murder of Avijit Roy in Bangladesh. Photograph: Munir Uz Zaman/AFP/Getty

Mukto-Mona, founded by Bengali-American activist Avijit Roy (1972-2015).

Immersive, digital experiences may sometimes feel profound, but rarely are they a matter of life and death. A tragic exception is Mukto-Mona (Freethinker), an online community founded in 2001 by Avijit Roy, an engineer who lived in Atlanta but remained deeply connected to his Bengali homeland. Refusing to be bound by “comfortable superstition, stifling tradition, or suffocating orthodoxy,” as he once put it, Dr. Roy embraced science, reason, and humanism. To religious fundamentalists, this can be considered blasphemy. On February 26, 2015, as he and his wife, Bonya Ahmed, were leaving a book fair in Dhaka, the capital of Bangladesh, they were set upon by Islamic extremists brandishing machetes. Dr. Roy was hacked to death; his wife was gravely wounded. The police stood by and watched.

The attacks didn’t stop there. On May 12, Ananta Bijoy Das, a blogger for Mukto-Mona, was butchered outside his house by four Islamic fundamentalists. On August 7, Niloy Chatterjee, also a blogger for Mukto-Mona, was slaughtered in his home in Dhaka by six machete-wielding assailants. On October 31, Faisal Arefin Dipan, the publisher of Dr. Roy’s last book, Biswasher Virus (The Virus of Faith), was hacked to death in his Dhaka office by Islamists. Remarkably, in the face of all this, Mukto-Mona survives. “In Bangladesh they are fighting machetes with pens,” Dr. Roy’s widow declared in a lecture before the British Humanist Society in London last summer. “Everywhere, we must fight fundamentalism and all oppression, with compassion and rationality and universalism, and with a deeper understanding of the conflicts. That is the twenty-first century challenge of humanism.”

Network Effect: Human Life on the Internet, created by artist/computer scientist Jonathan Harris and artist/engineer Greg Hochmuth.

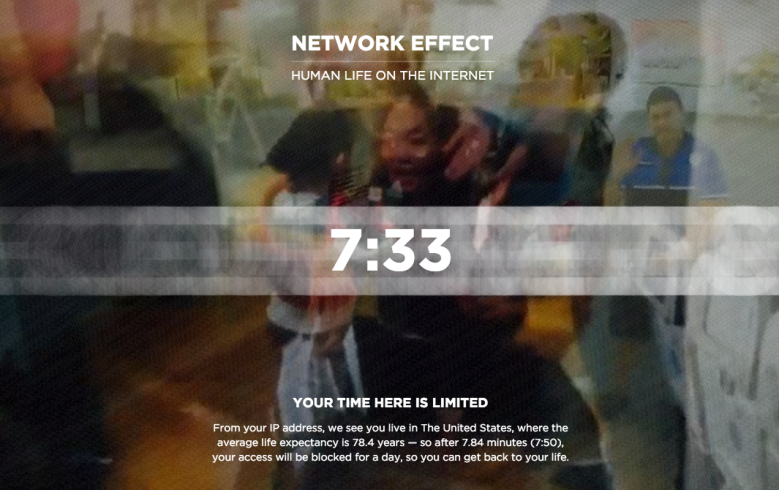

A network effect is the halo that results when each new user of a given service—the telephone, for example, or Facebook—inadvertently makes the service more valuable to others simply by joining it. But is this kind of value creation necessarily a good thing? “Network Effect,” which made its debut online in October, suggests that it may not be. “Once people come in, then the network effect kicks in and there’s an overload of content,” Greg Hochmuth, a software engineer who helped build Instagram, told The New York Times. “People click around. There’s always another hashtag to click on. Then it takes on its own life, like an organism, and people can become obsessive.”

To explore the consequences of this kind of behavior, Hochmuth and Jonathan Harris collected 10,000 YouTube snippets of people doing ordinary things—yawning, eating, falling, cuddling, 100 different actions in all. These were then trimmed, cropped, processed, sped up, layered with voice-overs, set to the sound of a human heartbeat, and transmuted into a stream of frenetic, anxiety-provoking activity. Users are not permitted to see the whole thing at once. Instead they see a message like this:

From your IP address, we see you live in The United States, where the average life expectancy is 78.4 years — so after 7.84 minutes (7:50), your access will be blocked for a day, so you can get back to your life.

The Pickle Index, created by Eli Horowitz and Russell Quinn.

With few exceptions, the e-book has yet to evolve into much more than a print book with less heft. But what if it were something else entirely? What if it took full advantage of its format to rethink the conventions of storytelling? Eli Horowitz, the former publisher of McSweeney’s, and Russell Quinn, its former digital media director, tackled this question in 2012 with The Silent History, a novel in app form about an epidemic that robbed children of their ability to use language. Now they have revisited the issue with The Pickle Index, a weirdly comic novel about, well, pickles. Specifically, about a totalitarian dystopia in which everyone has to eat pickles—and like it.

The Pickle Index is told in three forms (four if you count the Kindle edition): a conventional paperback book, a lavishly illustrated two-volume hardcover that tells the story from two distinct points of view, and a digital app that purports to be the actual, government-decreed Pickle Index in question, a recipe-exchange network that itself tells a story. With the books you are, as Horowitz has put it, “a human in the real world, reading”; the app puts you inside the story you would otherwise be reading about, providing what he calls “the thrill of discovery.” A word of warning about the recipes, however: Don’t.

This Is the Story of One Block in Bed-Stuy, Brooklyn, edited by Genevieve Smith, production by Sarah Caldwell and Abraham Riesman, design and development by Leslie Shapiro, Sarah Ruddy, and Kristen Dudish for New York magazine.

One of the biggest questions raised by digital journalism is also one of the most basic: How to tell a story? Freed from the linear progression of print, stories risk becoming confusing, disjointed, or—what may be worst of all—slavish imitations of their former selves. This is the dilemma New York magazine’s editors faced when they set out to tell the story of a single block in Bed-Stuy, the inner-city Brooklyn neighborhood that had been redlined by lenders since the 1940s but has now become a magnet for gentrification.

Billed as “a tale of epic change, in miniature,” “One Block” introduces readers to the residents of MacDonough Street between Patchen Avenue and Malcolm X Boulevard, where solid 19th-century brownstones that would have sold for $18,000 in the 1970s ($82,000 in today’s dollars) now go for upwards of $1.5 million. In this case it’s the print version of the story, presented in blocks of text, that seems disjointed; online, the nonlinear narrative feels fluid and natural. “You can read and hear the residents’ own stories in their own words as you travel down the block door-by-door,” the editors wrote in their introduction. “And the many connections between neighbors, memories, history, and sweet-potato-pie recipes are rendered here as literal links, digitally. The stories can be read in any order. Together, they reveal what it means to be neighbors on MacDonough Street, circa 2015.”

Columbia’s Digital Dozen for 2015 were selected by members and associates of the Columbia Digital Storytelling Lab:

- Lance Weiler, Founder and Director of the Digital Storytelling Lab and Director of Experiential Learning and Applied Creativity at Columbia University.

- Hilary Brougher, Associate Professor in the Columbia University School of the Arts Film Program.

- Ira Deutchman, Professor of Applied Practice in the School of the Arts Film Program.

- David K. Park, Dean of Strategic Initiatives at Columbia University, Member of Columbia’s Committee for Global Thought and the Columbia Data Science Institute’s Center for New Media, and fellow at Columbia’s Center for the Management of Systemic Risk.

- Frank Rose, Senior Fellow at the School of the Arts and Faculty Director of the executive education seminar Strategic Storytelling.

- Dennis Tenen, Assistant Professor of English and Comparative Literature and co-founder of Columbia’s Group for Experimental Methods in the Humanities.

- Paul Woolmington, Senior Fellow at the School of the Arts.